Usability and UX at the IML > UX

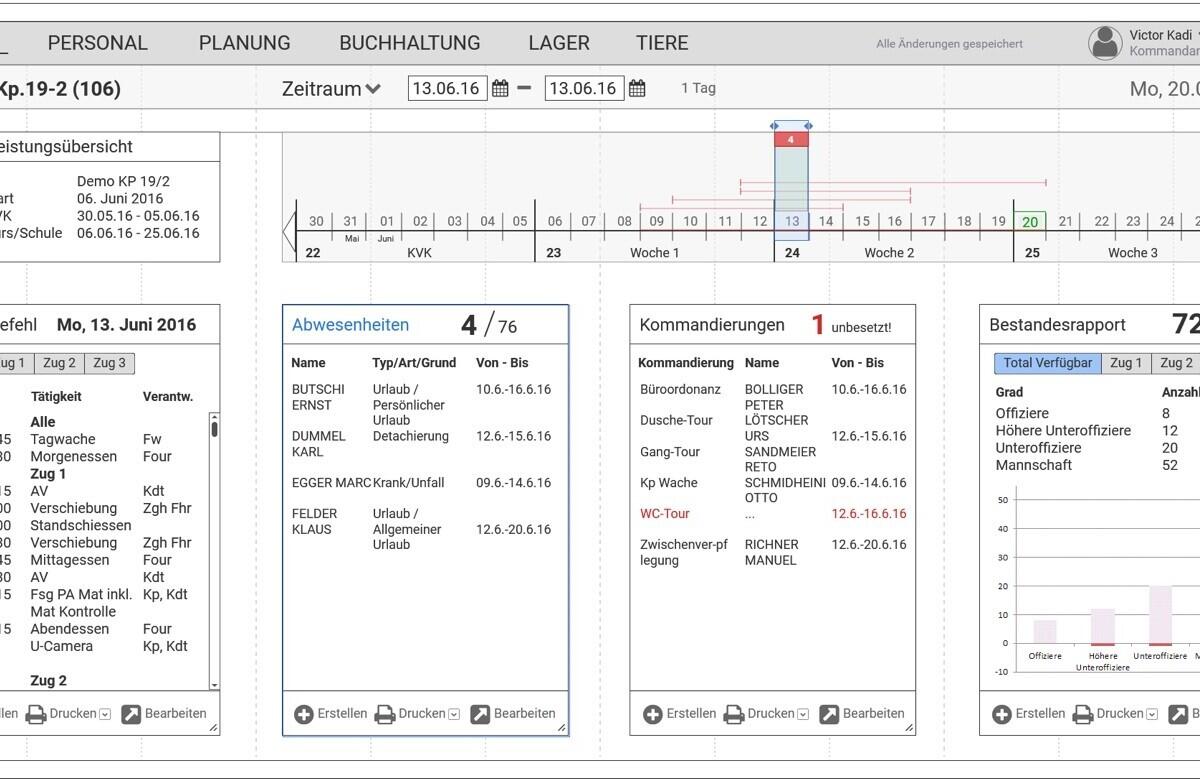

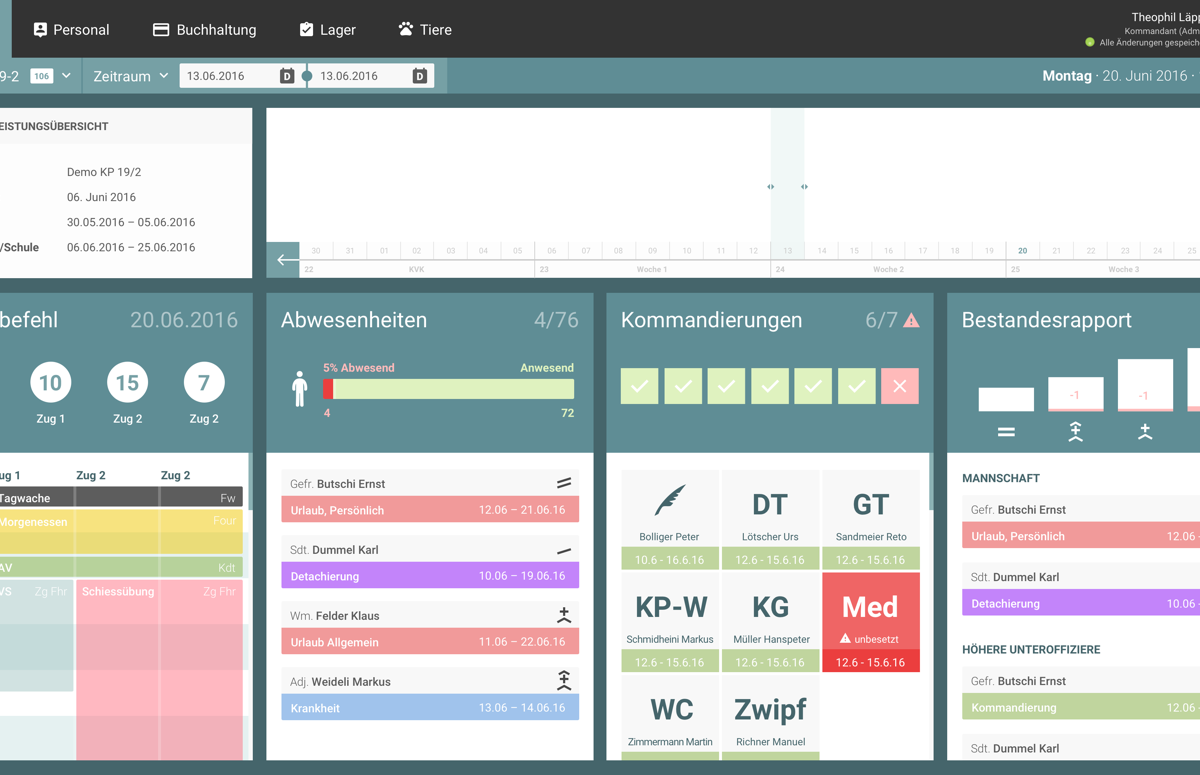

With the IML UX team (formerly U5), we have a very experienced and qualified team of UX experts at the IML. We have - for more than 15 years - been supporting and advising development projects at our institute (especially e-assessment and e-learning projects, but also various web-applications) and with diverse external clients.

Our focus lies primarily on projects in the fields of education, healthcare, and administration. However, we have also assisted Migros, UBS, SNF and other companies with projects in various phases.

If you are interested in Usability and UX services or would like to learn more about us, please visit https://www.uhochx.ch/.

In the following, we explain how we optimise the Usability and User Experience of our own products and those of our customers using proven methods and processes.

Terminology

Usability and User Experience are two challenging and interdisciplinary fields that play a central role in software, product, and process development. UX experts not only connect the stakeholders in the development process with each other (clients, developers, visual designers, users, etc.) and mediate between them, but also accompany the development through all phases: from brainstorming to testing after implementation with a wide variety of methods.

But what are Usability and User Experience? And what do experts in these fields actually do?

Usability is a quality measure that indicates how easy, efficient, and effective a software or product is to use. At the same time, the term Usability also refers to a discipline in which various methods are used to actively simplify and improve the use of a system.

A somewhat exaggerated definition has been expressed by David McQuillen: “Usability is about human behaviour. It recognizes that humans are lazy, get emotional, are not interested in putting a lot of effort into, say, getting a credit card and generally prefer things that are easy to do vs. those that are hard to do.[1]”

However, it was precisely aspects of the emotionality of users that received little attention in the early days of Usability (1980s). This is not surprising, since Usability methods advanced primarily from the field of Ergonomics. From the mid-1990s - and increasingly after 2005 - a somewhat more comprehensive view of the development and assessment of human-product interactions became established, the User Experience.

The term User Experience (UX) describes all impressions and experiences of a user during the digital and/or physical interaction with a product, service or institution over time.

Compared to Usability, the UX of a product is not easily measurable, as it also includes hedonistic aspects (e.g., joy, pride, frustration, etc.) and therefore eludes simple measurement scales.

Both disciplines have in common that they strongly refer to the User as the centre of all attention. This clear reference has its roots in User Centred Design (UCD), a philosophy or mindset propagated by Rob Kling in 1977[2], which made the user the centre of attention in product development (in contrast to the technology-centred approach that had prevailed until then).

Simplified, one can say that Usability is a component of the UX concept - an important component of UX, because without good Usability there will never be a good UX.

Phases of product development

But how can good UX and usability be achieved? What are the tasks of UX designers and Usability experts?

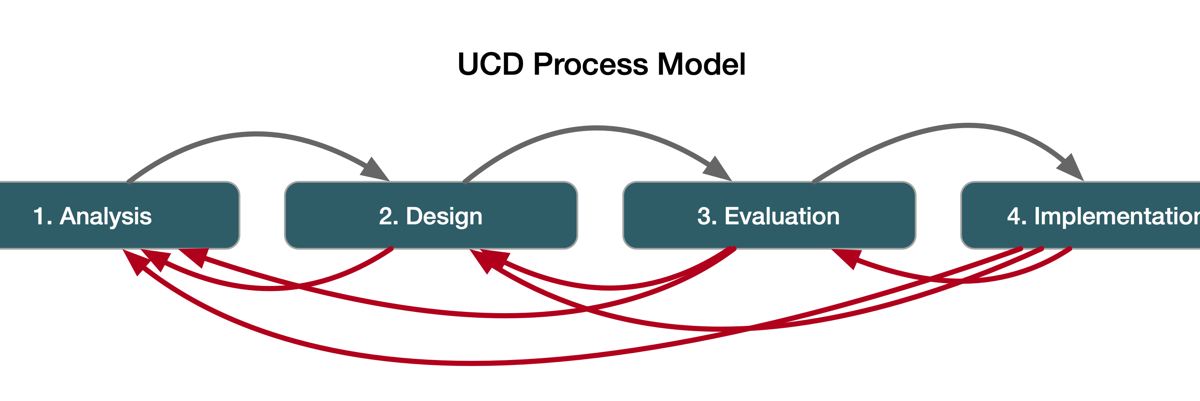

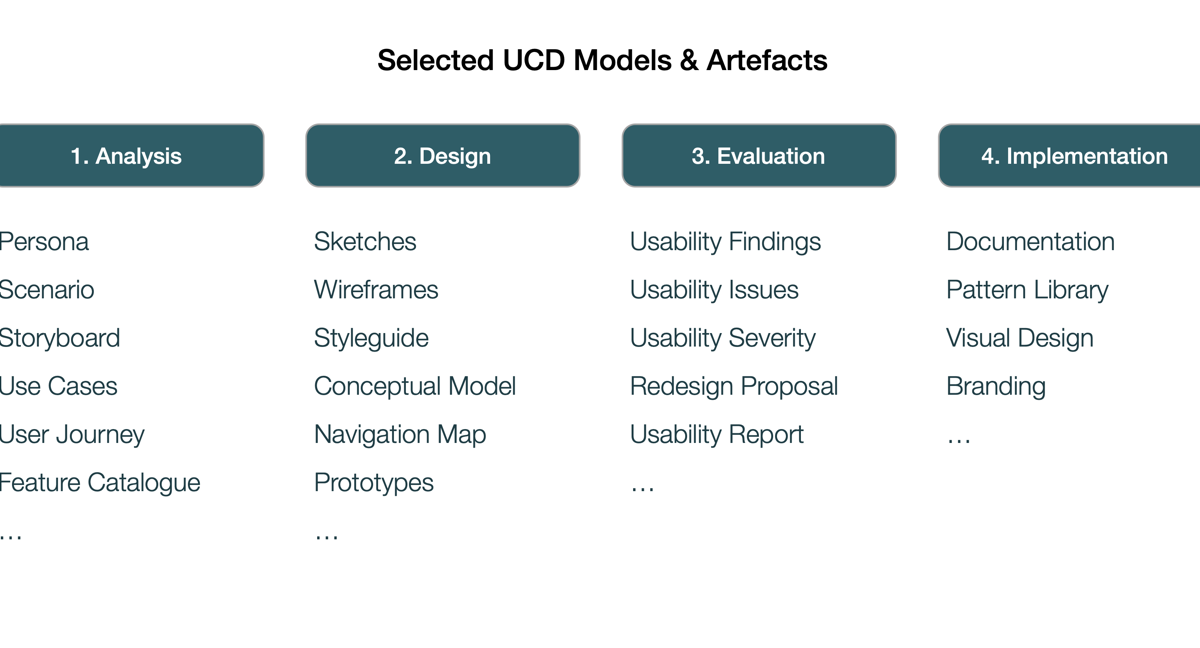

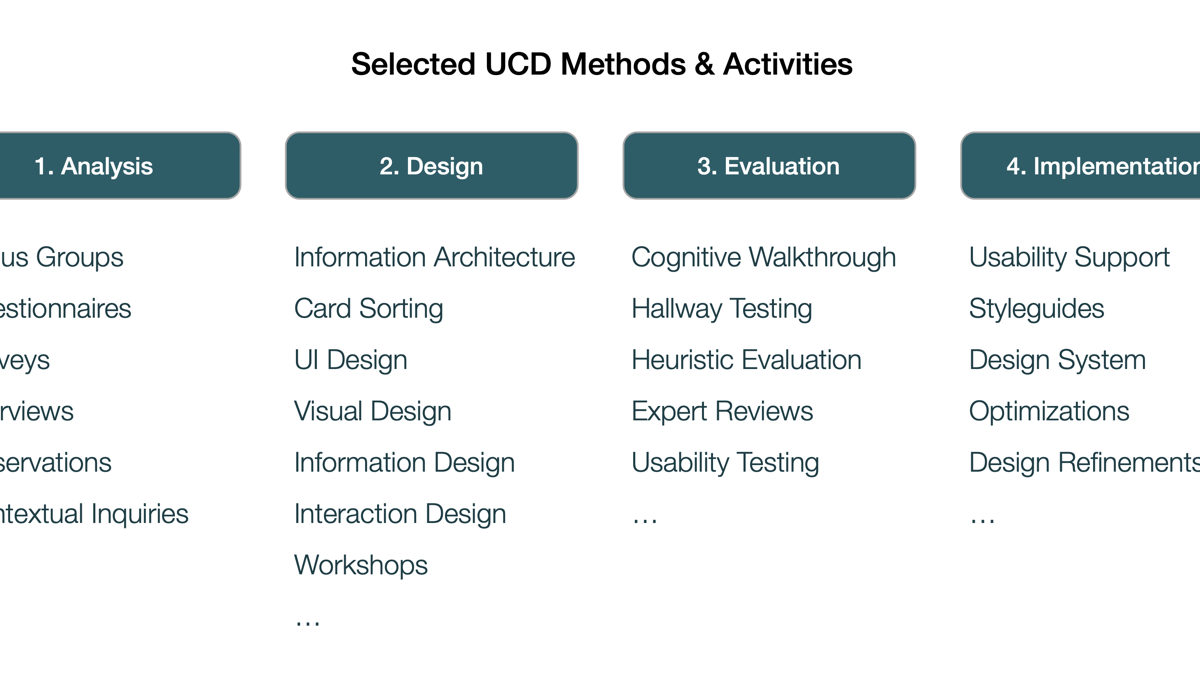

The best way to show the versatility of this profession is to take a closer look at the different phases of product development. There are different phase models, but in principle they are all similar and differ mainly in the level of detail and the names of the phases.

1. Analysis (understand/research)

In this starting phase, it is the task of UX professionals to precisely define the goals of the project together with the client. The user groups are identified (and maybe «personas» are created), existing products or competing products are analysed to find out the problems and expectations of the future users of the product (UCD), so that the system can be tailored exactly to their needs.

This phase is very important and is often underestimated (and instead based on the ideas of the company management), but it is essential in a UCD approach. Typical methods used in this phase are interviews, questionnaires, observations (e.g. in a «Contextual Inquiry» or «Shadowing», where the future users are accompanied and observed while working or using a product) or the analysis of existing user data, e.g. from a predecessor product, or the analysis of competitor products.

Afterwards, order must be brought into this collection of data. Conclusions are drawn from all the different sources, and priorities are set. While the data collection is usually done directly and exclusively by the UX department, the prioritisation must be done together with the stakeholders, not least the product owner. This phase of converging information is so important (and often lengthy) that it is seen as a separate phase in some phase models.

It is here necessary to work out what the most important needs, problems and requirements of the clients and management are, where the development should start and where the focus of the project should be.

2. Design (ideate)

This phase usually consists of many iterative phases because it is difficult to make a concise design based on data alone. Often there are dozens of possible solutions to a given problem, even at the conceptual level.

The work of UX is particularly important here: on the one hand, as many ideas as possible must be generated («ideate») about how a problem could be solved, a certain screen or dialogue could be designed, how the basic metaphor of the whole application could be built. On the other hand, it is also about showing the stakeholders in workshops examples feeling or looking as real as possible, e.g., with concrete sketches ("wireframes"), how these ideas would look on the screen.

Here, psychological, organisational, and creative skills are required from the UX experts, but also group leadership and finally decisiveness, to select a few, but target-oriented and concrete designs from the many ideas.

The degree to which designs or concepts are created in this phase varies greatly depending on the project and its maturity. During the workshops, often not much more than sketches or even just scribbled details with a pen are recorded. Often, it is then the UX's task to make detailed wireframes of all proposals by the next workshop to provide all participants with the same information level for further discussions.

However, it can also be the case that distinct visual designs are already created in this phase (e.g. because a style guide is already available) or even applications are already implemented with simple frameworks, e.g. if the interaction between the users and the system is central and it cannot be evaluated with static wireframes.

3. Evaluation (validation)

Sometimes the design phase cannot be distinctly separated from the evaluation phase, because the resulting designs are evaluated directly after a brainstorming session. Then design and evaluation alternate in short iterations.

Sometimes, however, the overall metaphor of the whole application must be created first and not details evaluated. Nevertheless, it is often necessary to select from several possible variants (there is always a multitude of possible solutions to a problem) the one that best meets the requirements of the users.

The evaluation is therefore preferably carried out again with the future users, because only they can say or show which solution is the most suitable. There are many different evaluation methods for this purpose, e.g.:

- «Guerrilla Testing» (tests not necessarily with the actual target group, but simply wherever you can find people who have a few minutes, e.g. in the cafeteria)

- Expert Evaluations (UX experts evaluate the various proposals on the basis of predefined criteria (heuristics))

- Cognitive Walkthrough (usually in a group, different tasks are solved with the test designs)

- Laboratory Evaluation (classical Usability Evaluation in a laboratory, possibly also with eye-tracking)

- and many more.

The choice of the appropriate evaluation method ultimately depends on the maturity of the design and the number of variants, as well as the available time and money budget.

Structured evaluations are a strength of the Usability discipline, as different metrics also produce comparable results that can lead to a concrete decision. As mentioned above, in the UX field it is much more difficult to compare, e.g. hedonistic attributes of different designs.

(3b. Iterations)

«Iterations» is not really a separate phase, because it can happen at any time in the UX process that one has to return to an earlier phase. For example, if it was noticed in the evaluation phase that none of the suggestions were satisfactory, then one must return to the design or even analysis phase. If you notice that information is missing or that there have been new developments in the environment (e.g. technological, social, economic), then you have to take a step back to analysis or even to additional data collection.

4 Implementation

And finally follows the actual realisation of the application, the implementation. Since this phase is usually time-consuming and correspondingly expensive, one tries to have already solved as many problems and eliminated as many ambiguities as possible in the first three phases.

Nevertheless, it is often not until this phase that a graphic designer is called in, a corporate design is created, and a decision is made as to which frameworks the programmers will work with. This means that the UX is once again called upon to draw real-life, pixel-precise screens from the Mockups and Prototypes of the previous phases - based on the design framework and in close cooperation with the Visual Designer and often also with marketing/management of the customer.

In this phase, the aim is to specify each element of the user interface (UI) so precisely that the developers do not deviate from it and that an overall coherent and attractive UI, and thus an attractive User Experience, is created and maintained in the final product.

UCD as a process

Today, newly planned products usually go through these phases. Unfortunately, clients often demand shortcuts and leave out some phases because of scarce resources, but most of the times, the resources saved are needed multiplied in later phases because the UX is not as great as expected. The described phases should also be implemented for the implementation of new features in an existing product, even if they are not always necessary step by step.

For products, especially software, there is no such thing as «it's finished», because environment, technology, competition, economic situation, user needs, the company goals or developer expectations of the software are constantly changing, hence it is always in a state of flux and thus UX support is necessary, even if the product is years old.

UX as a transdisciplinary discipline

The tasks and activities of UX experts are very diverse. In addition to creativity, a quick grasp of new fields of work, precise analytical skills or a flair for graphic design, it is above all the communicative skills that distinguish a good UX designer from a bad one.

In general, it is not uncommon for UX experts to have to keep all stakeholders on the path to the goal (or the vision) in the course of the (sometimes multi-year) project phases. Be it because there are personnel changes in the project team or because the stakeholders lose themselves in their particular interests after a certain time. It is often up to the UX to defend the continuous course of the project and a consistent project result, because it is indispensable for a good User Experience to always keep the wishes and needs of the users in focus and to consistently pursue the defined goals.

In each phase of the UX cycle, communication with different stakeholders in different roles is necessary:

- In interviews with users to get the desired information for the analysis

- Reflecting back to the client or "product owner" that the specifications or specified requirements are not sufficient

- Lead a workshop or focus group to ensure that useful information flows

- Negotiate with the programmers to what extent they have to or can fulfil the specifications

- Bring the right people together on a project, even if they don't know each other yet

- Approaching a stranger in the cafeteria for a guerrilla/hallway test

- Presenting a prototype (or several) to the management of a company and pointing out the pros and cons

- And last but not least, writing reports to make the information gathered accessible and understandable to third parties.

With all the different demands and ideas of the project stakeholders, the biggest challenge is to always follow up and defend the contact and wishes of the users - the most important stakeholders.

Anmerkungen

[1] David McQuillen in «Taking Usability Offline» Darwin Magazine, June 2003

[2] Kling, R. (1977). The organizational context of user-centered software designs. MIS quarterly, 41-52.